By Jose Corpas

Firpo was fulfilling the “dream of the Latin Race,” by attempting to become champion, wrote George Trevor for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. “Patriotism fortifies Firpo,” Trevor wrote. Trevor described Firpo’s diet. Each meal of the day was composed of red meat and fruits along with six eggs – a diet that would “wreck a modern man’s digestion in quick order,” he concluded.

“Firpo’s teeth, stomach, and assimilative organs are not those of a modern man. The cave man utilizes 6,000 odd food calories per day. It does not take more than 3,000 calories to keep Dempsey going.”

Trevor was only warming up. “Americans do not realize the intense racial hatred for the United States underlying the polite veneer which cloaks the secret thoughts of our Latin neighbors,” he wrote. Those peoples, he wrote, have always “passionately yearned for a champion who could fight with his fists in the virile fashion of the North.”

Dempsey became a symbol of U.S. imperialism. It was a time when American occupation was either taking place, or had recently taken place, in Nicaragua, Honduras, and Veracruz. The Banana Wars were ongoing and the memory of American William Walker, the self-proclaimed President of Nicaragua, and his attempt – with the blessing of Pres. Franklin Pierce – to turn Central America into the new American South where slavery existed, was still fresh. A win by Firpo would be a small victory over imperialism.

ALSO READ: Part 1: 100 years after Firpo’s epic fight with Jack Dempsey

Luis Angel Firpo was born a sickly child in Junin, Argentina in 1894. An ear condition that later disqualified him from serving in the military caused him constant pain and dizziness. Doctors in Buenos Aires alleviated much of the pain, but the dizziness and lack of balance continued into adulthood. If asked to cross his arms in front of his chest and close his eyes while raising one leg off the ground, he may have toppled over for a ten count.

Standing 6’3’ tall, with hands that could conceal a grapefruit, Firpo was twenty-two when he started boxing. Because of him, boxing would become a staple of Argentine sports. In his day, Chile was the boxing hotspot. Continuing in boxing meant going to Chile. Today, Buenos Aires to Santiago is a two-hour flight in good weather. Back then, Firpo had to travel by foot.

He walked ten hours per day, taking the route of the muleteers, until he reached the foot of the Andes, sometime sleeping against a rock or tree, more concerned with avalanches then he was with a potential encounter with an Andean Bear. At times, he crossed the jagged range on a donkey. He arrived about a month later, a few pounds lighter, his skin a few shades darker.

His fighting style was hindered by his poor balance. He took short steps in the ring but was quick to find the correct pivot that placed him in position to land his secret weapon. It was a right-hand punch, thrown straight. When it landed, Firpo would leave his arm outstretched and glance at the legs. If the legs quivered, he’d put all his weight into his arm and extend the punch a few more inches into something that was almost a push. He called it the Firpazo and it was responsible for most of his wins.

For some of those wins, he was paid in cranberry beans, which he later resold in Argentina at a profit. Firpo then asked to be paid in books on investing. He read every page of every book and kept the better ones, sold the rest. When he arrived in Newark for his first bout in the United States, he brought with him all the knowledge he attained from those books, and the Firpazo.

His first fight received scant coverage in America. In Latin America, it was box office gold. Firpo insisted on getting the Latin American film rights to the match. He showed up to the fight with one trainer carrying a towel, the other a camera. Film of that fight was played throughout Central and South America and made Firpo a small fortune. When 1923 came, he was as famous as Dempsey.

It was hours before the opening bell, the temperatures were in the sixties and the streets around New York’s Polo Grounds were filled with men in dark suits and light hats. The announced attendance was 85,800 with about half holding binoculars. An estimated 25,000 more were left outside looking for ways to sneak in.

Pushing his way through the masses was Firpo. With everyone in front of them anxiously trying to get in and not wanting to risk losing their place in line, they did not notice that one of the men they came to see was standing behind them. He was trapped in the crowd until, “four large Irish cops noticed,” Firpo later recalled. Using their clubs against the legs of those who did not move, they forced open a path.

Firpo and a night to remember forever

Following a slight delay to allow Dempsey to re-wrap his hands after duct tape was found on his bandages, the fighters entered the arena. The champ came into the ring wearing all white while Firpo concealed his injured left arm under his familiar yellow and black checkered robe with the purple collars. While Firpo’s right hand ranks amongst the hardest in history, the left was thrown in a pawing fashion, used to gauge if he was close enough to land the right. He can’t beat Dempsey with one hand, the experts said. So, they worked overtime on the left during training, at times, throwing nothing else. One of those lefts, thrown full force against a cement filled heavy bag, sent a sharp pain from the elbow up to the shoulder.

The humerus was fractured, some said. It was later revealed to have been dislocated. The promoter, in front of the commissioner and with writer Nat Fleischer present, told him it was too late to cancel. They summoned a Dr. Walker, who rubbed ointment on the arm then pulled, massaged, and yanked it into place. Twenty-four hours was not enough time for it to properly heal. Firpo would have to fight with one good arm.

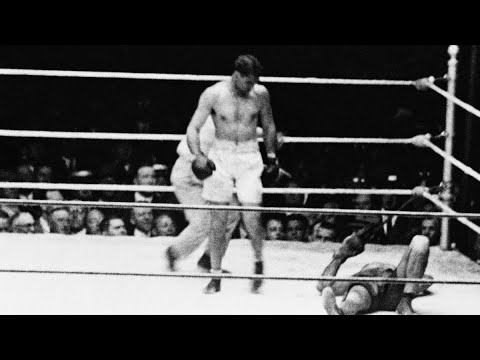

The bell rang and everyone from New York to the tip of Tierra Del Fuego slid to the edge of their seats. Dempsey went down. The crowd rose to their feet and the band that was in the front rows stopped playing. Dempsey used Firpo for a ladder and climbed up quickly. Then Firpo went down.

Again, Firpo went down, this time in that squatting position that sprinters get into when they say, “On your marks, get ready…”

There was fouling and clinching and each time Firpo went down, Dempsey hovered over him like the Farnese Hercules.

Dempsey went down, briefly, but the referee missed it.

Firpo goes down.

He’s up. Seconds later, he goes down again.

Dempsey is supposed to go to a neutral corner but doesn’t. The referee is not enforcing the rules. A five-week suspension awaits him after the fight.

Firpo is down. The referee counts slow. Firpo is up at “9.” It felt like “11.”

Firpo gets dropped again, landing in a dogeza pose. About two seconds after rising, a left hook puts him down again, on his side, resting on his bent elbow as if he was at a picnic.

They fell into a clinch as soon as the Argentine got up. Dempsey stalked him, his dangling at his waist. He soon paid the price for not protecting himself. A right from Firpo lands by the ear and rocks the champ’s head to the side. The champ tries to clinch, but Firpo pulls his arm back. Dempsey resume stalking, this time a little bit slower and a lot more cautious. A heavy right to the body by Firpo followed by a right to the head forces Dempsey to back up towards the ropes. He’s hurt. Dempsey covers up. He’s not fighting back. Another hard right lands, and then it happened.

The right lands. One of Dempsey’s legs comes off the canvas. Firpo turns the right into the Firpazo. It sent the champion headfirst out of the ring. Dempsey lands on a reporter’s typewriter. His back will hurt him for the rest of his life.

Some say the count reached ten. Others say fourteen, even seventeen seconds. The referee said nine. Firpo thought the fight was over. He had relaxed and his adrenaline dropped.

The telegrams reach Latin America. Dempsey was knocked out of the ring, was the message.

A blue light goes on at the top of the Palacio Barolo.

There’s dancing in the streets of Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Puerto Rico, Guatemala, and Mexico. In Usulután, a soccer team has a new name. In Junin, a nine-year-old Julio Cortázar celebrates with his family.

Then the light turned red.

The reporters at ringside helped push Dempsey back into the ring. The fight continued. Nat Fleischer, editor of The Ring magazine, said Dempsey should have been disqualified. Firpo’s handlers protested but the only ones who paid attention were those who understood Spanish. The fight continued. Firpo missed. He missed again. The round ended.

During the 60-second break, Dempsey has smelling salts shoved under his nose, and Firpo, one by one started feeling the effects of Dempsey’s punches. Thirty seconds earlier, he was ready to lift his arms in victory. Now, he could barely lift them for round two. Dempsey, revived, rushed out at the bell ready to conquer. Firpo was like a Mayan soldier slinging rocks at armor.

A mob threatened to burn down the American embassy in Buenos Aires that night. The writer, Cortázar, recalled that “15 million Argentines called for a declaration of war” against the United States. It was a “national tragedy,” and many “asked to break diplomatic relations with the United States,” he wrote.

Firpo never got the promised rematch. Instead, he fought another boxer who also never got his promised shot at the champ – Harry Wills. Against Wills, an African American, Firpo later commented on how he was treated for that fight. “Suddenly I was the ‘White’ fighter,” he said while describing how police stopped and frisked the black fans while hundreds of firemen parked outside the stadium with their hoses ready.

Firpo went on to run a successful chain of new car dealerships in both Argentina and Uruguay. Every year, on the anniversary of the big fight, Argentina remembers him with a holiday that is in his honor. Four streets in three cities bear his name and dozens of boxers and wrestlers, including Pampero Firpo, paid homage to him by calling themselves Firpo something or other. Whenever they boxed or wrestled, the chants were heard.

Firpo! Firpo! Firpo!

They’re still heard today.

Forward Raúl Peñaranda Contreras is on the attack. He has a clear view of the goal but there’s two defenders closing in on him. He gets ready to kick. The crowd erupts into cheers and that hundred-year-old chant. White noise covers the streets around Sergio Torres Rivera Stadium. That night, and every other night in Buenos Aires, when the blue skies above the Palacio Barolo fade to black, a light goes on at the top of its tower. It’s a white light but, from a distance, it looks blue.

La entrada Part 2: 100 years after Firpo’s epic fight with Jack Dempsey se publicó primero en UNANIMO Deportes.